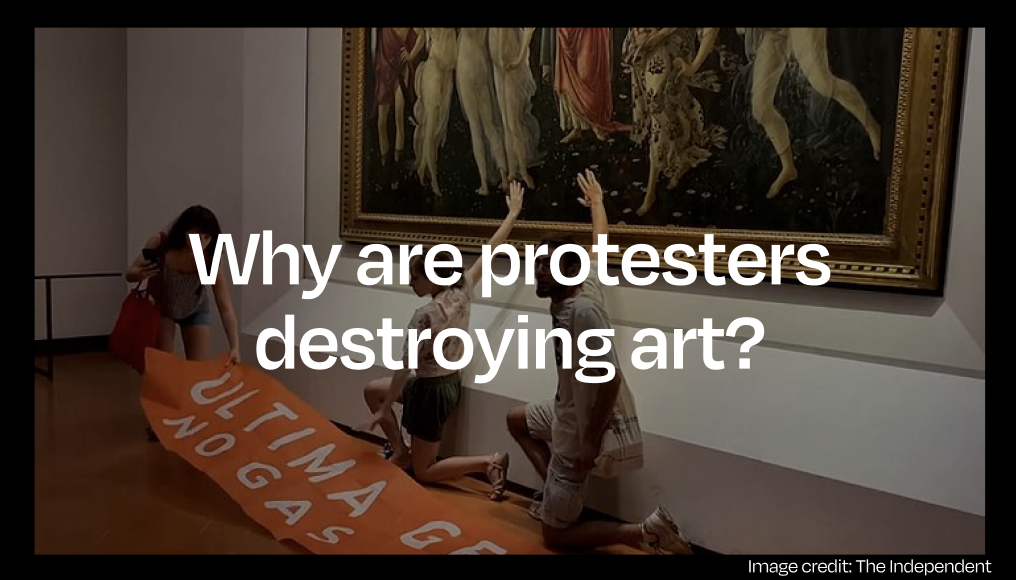

A Deep Dive into the Popularity of Abstract Art

Abstract art, with its evocative forms, vibrant colours, and exciting compositions, has captured the imagination of artists and art enthusiasts for over a century. Its popularity continues to grow as it surges through cultural boundaries and generations.

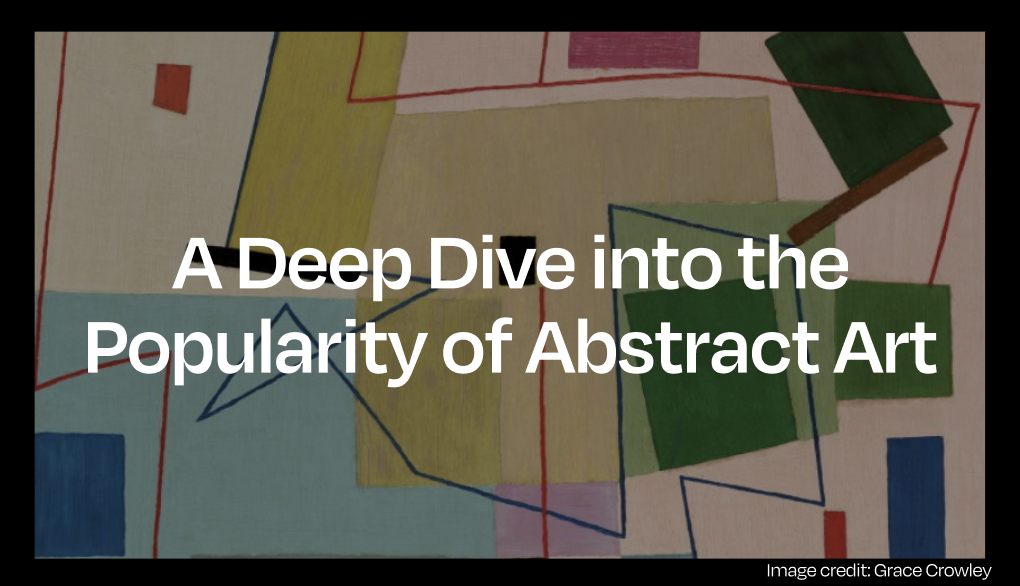

Abstract art is a style of artistic expression where the artist doesn’t aim to represent the physical world in a realistic way. Instead, abstract artists use colours, shapes, lines, and forms to convey emotions, ideas, and concepts.

In abstract art, you won’t find easily recognisable objects or figures; it’s more about the feelings and thoughts that the art evokes.

Imagine looking at a painting filled with bold, swirling colours and interesting shapes. In abstract art, these elements might not represent anything specific like a tree or a person. Instead, they’re like a visual language that speaks directly to your emotions and imagination. It’s all about interpreting the art in your own way, allowing you to connect with it on a personal and often deeply emotional level.

The Beginnings of Abstraction

The roots of abstract art can be traced back to the early 20th century when artists began to break away from traditional forms and explore new creative ways to express themselves. Wassily Kandinsky, often regarded as the pioneer of abstract art, played a pivotal role in this movement. His early paintings are considered some of the earliest examples of non-representational art, where colour and form took precedence over depicting recognisable objects.

Wassily Kandinsky was born in Moscow in 1866, he initially pursued a career in law and economics before making a dramatic shift toward the world of art. Kandinsky’s journey into abstraction was marked by a profound desire to explore the spiritual and emotional aspects of art, breaking away from the constraints of realistic representation.

Kandinsky believed that art should speak directly to the soul and emotions, transcending the limitations of the material world. His writings, particularly “Concerning the Spiritual in Art” (1910), provided a theoretical foundation for abstract art, emphasising the spiritual and emotional aspects of artistic creation.

The Popularity of Abstract Art

Abstract art’s popularity endures for some pretty cool reasons. It doesn’t tie you down with concrete subjects or rules; it’s all about letting your emotions run wild. In abstract art, shapes and colours are like an emotional playground, and you get to be the explorer, finding your own meaning in the chaos. Unlike art that spells everything out for you, abstract stuff lets you write your own story, making it super relatable for just about anyone.

Abstract art also doesn’t play the time or culture game. So whether you’re from today or a hundred years ago, abstract art still speaks your language. Plus, abstract artists are always trying out new stuff, pushing the art world’s boundaries. This keeps things exciting and fresh, especially if you’re into avant-garde adventures. So, in a nutshell, abstract art is all about the feels, freedom, timelessness, and a dash of artistic rebellion.

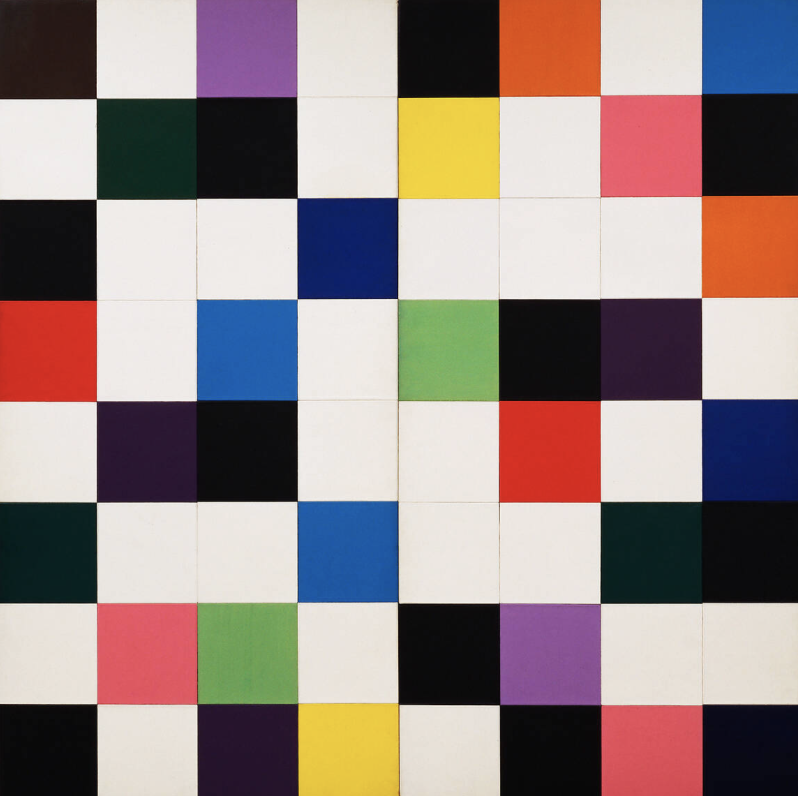

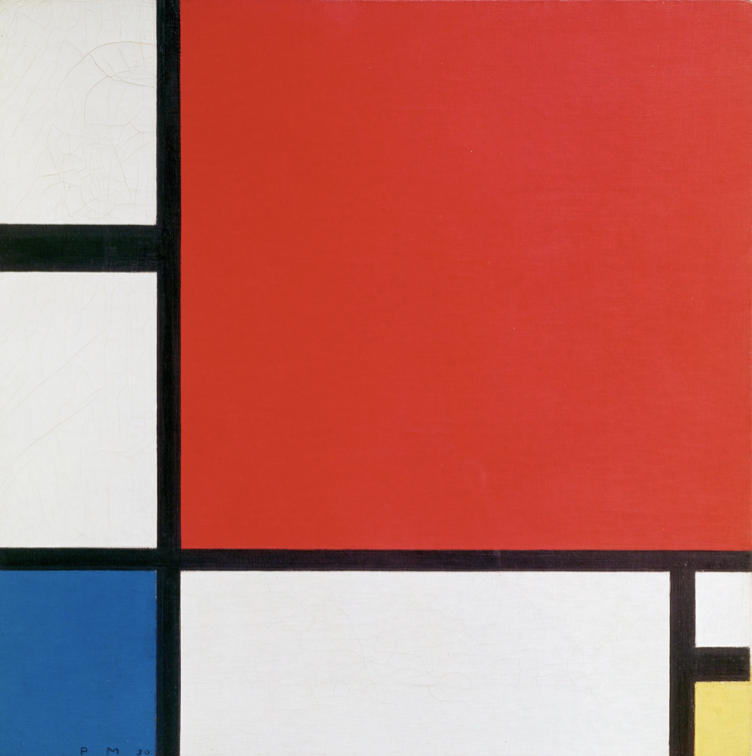

Consider the geometric compositions of Piet Mondrian, characterised by bold lines and primary colours. Mondrian’s works, such as “Composition II in Red, Blue, and Yellow” (1930), distill art to its fundamental elements of form and color. These iconic works remain as striking and relevant today as they were nearly a century ago. Abstract art’s capacity to bridge temporal gaps and resonate with viewers from diverse backgrounds contributes significantly to its enduring popularity.

The Controversies of Abstract Art

Abstract art has been both celebrated and critiqued since its inception. Its bold rejection of traditional artistic conventions, including the depiction of recognisable objects, has sparked numerous controversies and debates within the art world and beyond.

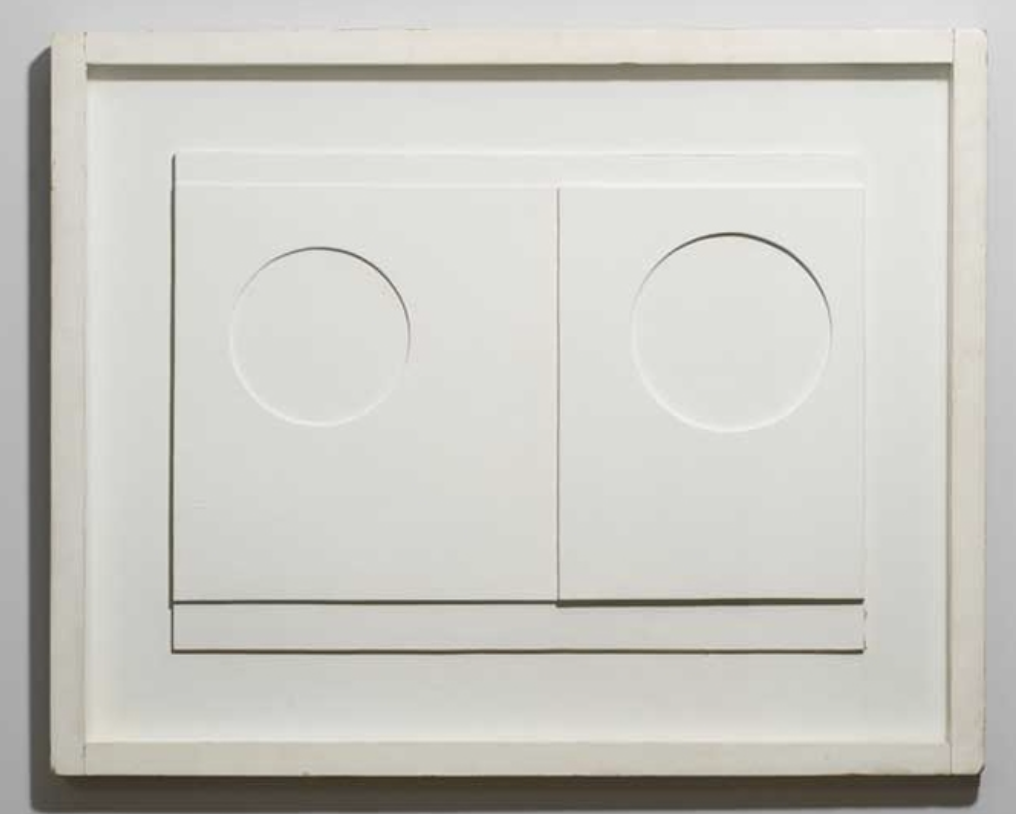

One of the earliest controversies surrounding abstract art revolved around questions of skill and technique. Traditional art had long been associated with precise draftsmanship, realism, and mastery of technique.

Abstract art’s abandonment of these conventions led to accusations that it lacked the technical prowess of traditional art forms. Critics argued that abstract artists were often masking their lack of skill with what appeared to be random brushwork and non-representational forms.

However, this critique misses the point of abstraction. Abstract artists deliberately sought to break free from the confines of traditional technique, aiming to convey emotions, ideas, and concepts in ways that transcended the need for precise representation. The seemingly spontaneous brushwork and unconventional techniques were not a sign of incompetence but a deliberate choice to explore new realms of artistic expression. In this sense, the controversy surrounding skill and technique in abstract art can be seen as a misunderstanding of its fundamental objectives.

The “My Kid Could Do That” Critique:

Abstract art has often been a target of public review and scrutiny, with critics suggesting that the lack of recognisable subject matter makes it seem simplistic. The infamous “my kid could do that” critique is often levelled at abstract art, implying that the work lacks the depth and skill associated with traditional art forms.

However, this critique fails to acknowledge the thought, intention, and artistic exploration that goes into abstract works. Abstract artists often spend years developing their style and experimenting with different techniques to convey complex emotions and ideas. The apparent simplicity of abstract art can be deceptive, as it conceals a depth of artistic exploration and innovation that is not immediately apparent to casual observers.

Famous Abstract Artists and their most Famous Paintings

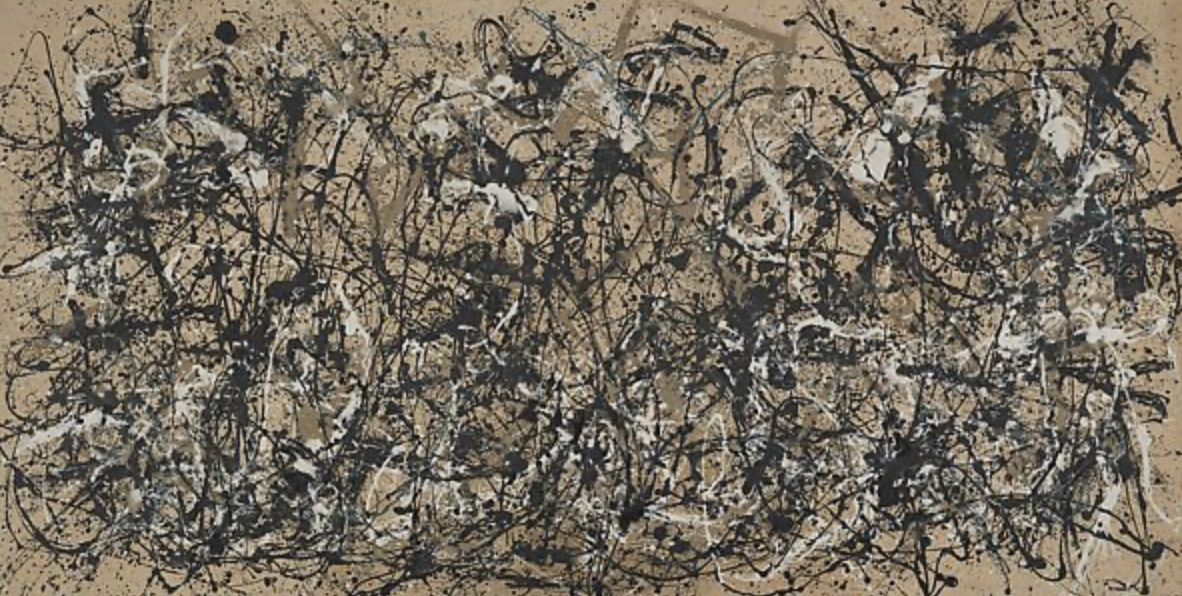

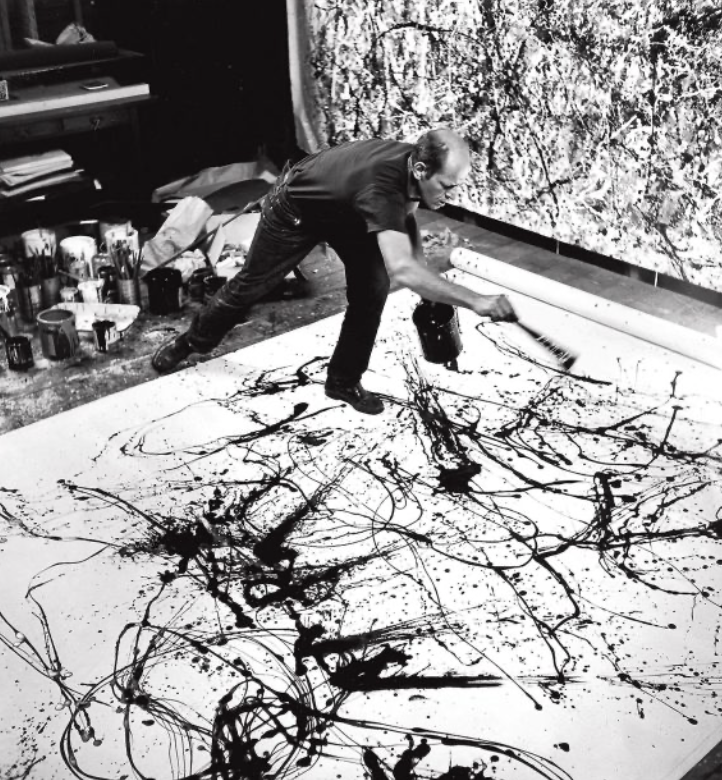

Jackson Pollock – “Autumn Rhythm” (1950)

Jackson Pollock’s “Autumn Rhythm” (1950) is a dynamic and groundbreaking example of abstract expressionism.

Pollock’s unique “drip painting” technique involved applying paint directly onto the canvas in a spontaneous and uncontrolled manner.

The result is a mesmerising web of interconnected lines, shapes, and colours that seem to capture the energy and movement of the artist’s creative process.”Autumn Rhythm” is a testament to Pollock’s belief that the act of creation was as important as the final artwork itself. It invites viewers to witness the artist’s physical and emotional engagement with the canvas, blurring the lines between artist and artwork. Pollock’s approach redefined the boundaries of what art could be, and “Autumn Rhythm” remains a testament to his revolutionary spirit and artistic vision.

Piet Mondrian – “Composition II in Red, Blue, and Yellow” (1930)

Piet Mondrian’s geometric abstractions, characterised by bold lines and primary colours, have become synonymous with the De Stijl movement. “Composition II in Red, Blue, and Yellow” (1930) stands as a paradigmatic example of his style. In this work, Mondrian distilled art to its essential elements, reducing it to a grid of primary colours and black lines.

Mondrian’s genius lay in his ability to create a sense of harmony and balance within this seemingly austere framework. “Composition II” embodies the idea that abstraction can communicate complex ideas and emotions through simplicity and precision. It is a visual manifestation of Mondrian’s quest for universal harmony, making it an enduring symbol of the De Stijl movement and a masterpiece of modern abstraction.

Mark Rothko – “No. 14” (1960)

Mark Rothko’s colour-field paintings, such as “No. 14” (1960), are celebrated for their profound emotional depth and meditative qualities. In “No. 14,” Rothko explores the interplay of color and form in a way that invites viewers to immerse themselves in the experience of pure abstraction.

Rothko believed that colour could convey complex emotions and create a sense of spirituality. “No. 14” is a luminous canvas of rich, saturated hues that seem to vibrate with emotional intensity. The work’s vast, monochromatic fields of color invite viewers to contemplate and meditate upon the profound emotions it evokes. Rothko’s mastery of color and composition has left an enduring mark on abstract art, and “No. 14” stands as a masterpiece of contemplative abstraction.

Check out top-rated local artists near you!

Are you an artist ? Sign Up